Women as readers

Although Chinese literature was generally off-limits to women in the Heian period, the daughters of noble families were encouraged an expected to study Japanese literature, especially waka, a style of Japanese poetry. After Murasaki completed The Tale of Genji, the text became a manual of poetry for both men and women for centuries. According to the poet Fujiwara Shunzei, “to compose poetry without having read Genji is deplorable”.[1] And he may have been right: The Tale of Genji has been a cornerstone of Japanese literary canon for a thousand years.

As early as the twelfth century, women such as the author of Sarashina Nikki read, shared, and gushed over Murasaki’s tale. The author of Sarashina Nikki, known as Takasue’s daughter, grew up listening to the women in her family retelling favorite sections of Genji’s story, but she did not have access to the complete text — 54 volumes — until she received it and other books as a gift from her aunt.[2] It took less than a hundred years for Genji to achieve circulation outside the court, but it seems a complete collection was still hard to come by, even for a nobleman’s daughter.

By the Sengoku (Warring States) period (1467 - 1615), Genji was a standby for aristocratic women, such as Keifukuin Kaoku Gyokuei, the daughter of Konoe Taneie, a nobleman and poet who trafficked in manuscripts to support his household during the Sengoku period.[1] Exposed to Genji from a young age, Gyokuei produced several commentaries on the classic tale to guide her fellow woman reader. Many of her male contemporaries wrote about Murasaki’s references to Chinese poetry and the literary merits of her work, subjects that would have been inaccessible to women without an education in Chinese. Gyokuei eschews this approach, expressing her hopes for her readers in the Kaokushō:

And so for the sake of us foolish women, I have written this work and bound it up in four volumes. On an autumn evening or a snowy morning, as you think back and your heart goes out [ to the Genji], you can consult this in conjunction with the text.—Keifukuin Kaoku Gyokuei[1]

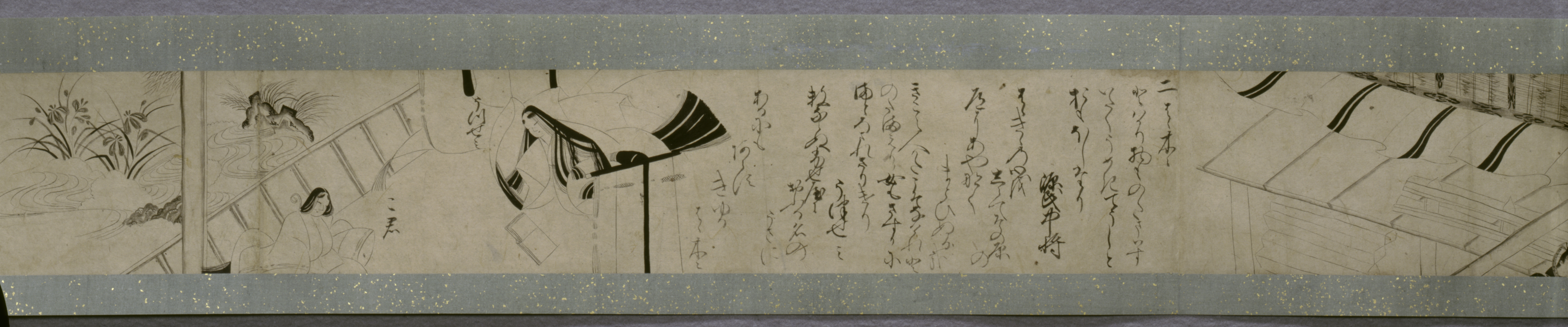

Her commentaries are largely focused on archaic vocabulary and Chinese terminology that an Edo-period noblewoman would have been unfamiliar with, with the aim of helping them follow the story for their own enjoyment rather than improving their poetry. Due to her small audience, her commentaries were never published in print, but they circulated in manuscript form until the 20th century. Among her readers was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a samurai and feudal lord who succeeded Oda Nobunaga in unifying Japan during the warring states period.[3] And like her Heian predecessors, Gyokuei was an artist as well, illustrating her own Tale of Genji emaki in the hakubyō (black and white line drawing) style. Gyokuei expresses her philosophy of the simple enjoyment of great literature best:

After all, the reflection of the light of the moon in the waters of a shallow well is no different from that in a deep spring.—Keifukuin Kaoku Gyokuei[1]

Footnotes

- G. G. Rowley, “The Tale of Genji: Required Reading for Aristocratic Women”, in The Female as Subject, edited by P. F. Kornicki, Mara Matessio, and G. G. Rowley (Michigan: University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies, 2010).

- Takasue's daughter, Sarashina Nikki [Sarashina Diary], trans. by Annie Shepley Omori and Kochi Doi (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1920), 19.

- Masako Mitamura, "The Samurai and Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji), in Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 88, no. 1/4 (2014): 56-69.