Development of writing in Japan

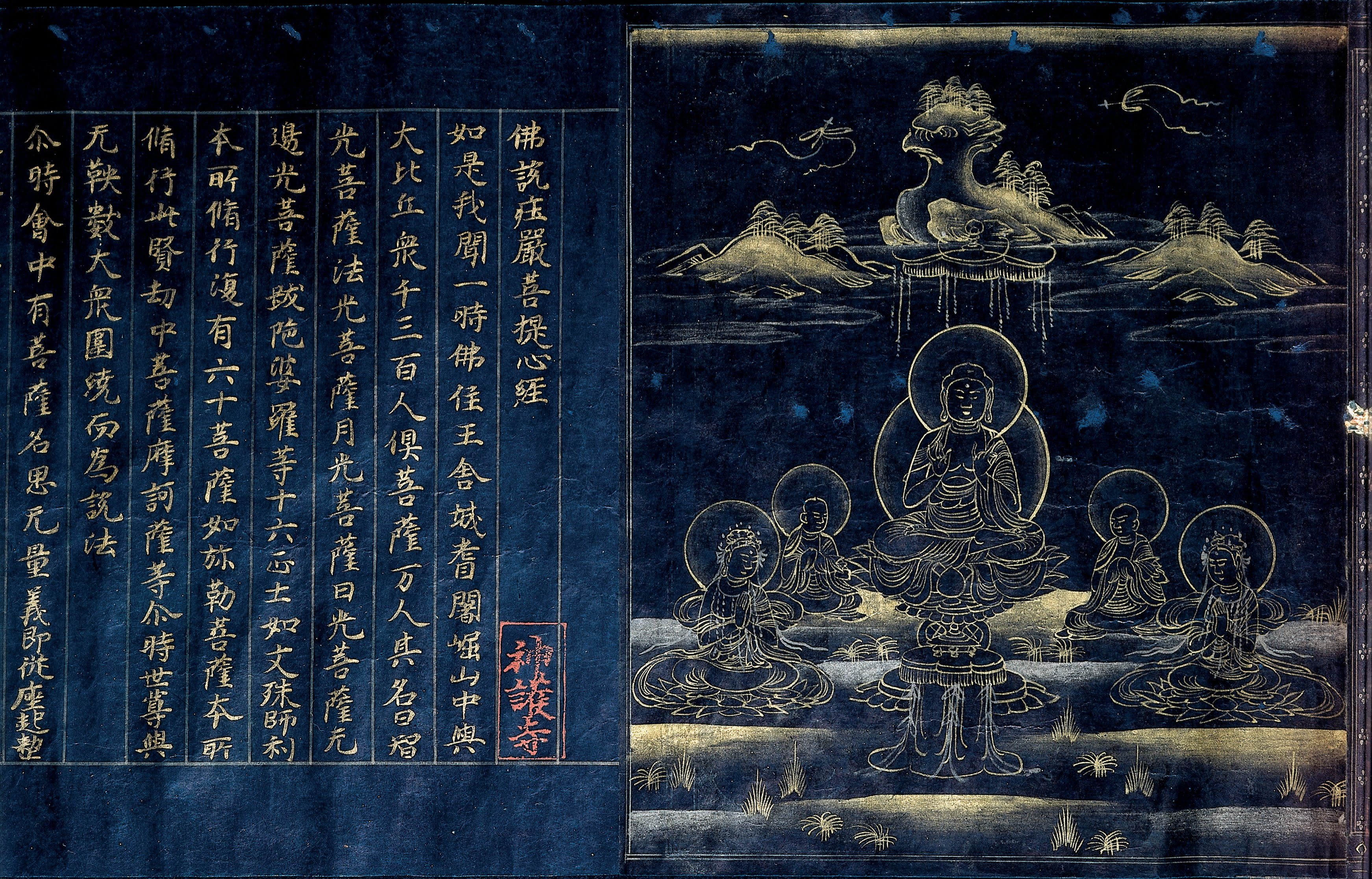

Writing was first brought to Japan around the 7th century by Chinese and Korean scribes, who used Chinese characters to write historical records, Buddhist texts, and Chinese classics. Scribes made various attempts to write the Japanese language using Chinese characters, such as man'yogana (万葉仮名), a script that uses the phonetic pronunciation of Chinese characters to render Japanese syllables. Man'yogana is named after Man'yōshū (万葉集, 'Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves'), the oldest extant collection of Japanese waka poetry.[1]

However, many Chinese characters are complex to write, and the sounds of the Chinese language are very different from those of Japanese, so scribes began developing a shorthand version of phonetic characters, which were dubbed kana (仮名, 'provisional characters'). This reduced the number of characters needed to write Japanese to a few hundred, which became a highly developed writing system during the Heian period (794-1185).

|

|

Writing in Chinese retained a special status amongst the elite of Japanese society, and it continued to be the primary language of government records and Buddhist texts for hundreds of years. In fact, the current imperial era, Reiwa (令和), is the first era name in Japanese history that was not derived from Chinese poetry.[2] In its early history, writing was also gendered, with Chinese considered masculine and kana considered feminine - Murasaki Shikibu herself references the term onnade (女手, 'women's hand'), a common epithet for kana.[3]

Footnotes

- Peter F. Kornicki, The Book in Japan, (Leiden: Brill, 1998).

- Elaine Lies, "New Japanese Imperial Era 'Reiwa' Takes Name From Anciety Poetry", Reuters, March 31, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-japan-emperor-idUSKCN1RD13X

Takahiro Sasaki and Wataru Ichinohe, Japanese Culture through Rare Books [MOOC] (FutureLearn, 2016). https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/japanese-rare-books-culture